I am very passionate about undoing what these slave ads helped to do – tear families apart. I am continuously fascinated at how DNA can help to prove and rebuild some family relationships, that were permanently severed during slavery, when even the basics of DNA and genetic genealogy are interpreted correctly. This is another one of those cases.

Often, I hear many conclude that a single DNA match confirms that someone was a parent, sibling, son, daughter, etc. But does it really confirm? It can add to the body of evidence gathered. However, an important and often ignored rule of genetic genealogy is that one DNA match alone doesn’t really “confirm” anything, especially in more distant relationships. It just might be a case where that single DNA cousin inherited identical DNA from a different ancestor in your lineage. I have had this to happen on several occasions, after looking at the shared chromosome segments on a chromosome browser and with DNA triangulation.

Researchers aren’t often able to benefit from the use of a chromosome browser (and DNA triangulation), that’s deemed an essential tool in genetic genealogy. AncestryDNA, the largest autosomal DNA testing company of the Big Four (i.e. 23andMe, MyHeritage, and FTDNA), does not provide its customers with a chromosome browser. The other three companies do. Nonetheless, since many people are taking the AncestryDNA test, estimated at 15 million to date, having multiple shared DNA matches who all descend from a common ancestor can definitely help to confirm or identify family relationships. That’s why researchers are often advised to analyze the family trees of their DNA matches or build them out further, if possible.

The frequency of related matches won’t be coincidental. Studying the family trees of shared DNA matches is especially helpful with slave ancestral research, where researchers are often faced with not finding sources that emphatically state that a particular enslaved person was a parent, sibling, son, daughter, spouse, etc. A number of sources do, like a Civil War pension file, a Freedman Bank application, a slave narrative, a court record, or when an enslaved family is noted in a will or slave inventory, etc. If only we can find one or more of these sources for ALL of our enslaved ancestors. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case.

That said, I have revisited the case of my mother’s great-great-grandmother. Her name was Margaret Milam, but the 1870, 1880, and 1900 censuses show that she was primarily known as Peggy Milam. Census records also report that she was born in Tennessee c. 1830. I determined that an Alabama native, Joseph R. Milam of Tate County, Mississippi, was the last enslaver of her, her children, as well as Wade Milam, the documented father of most of her children. I have shown in past blog posts that the death certificates of two of her children show two different maiden names for her – BRISCOE and WARREN.

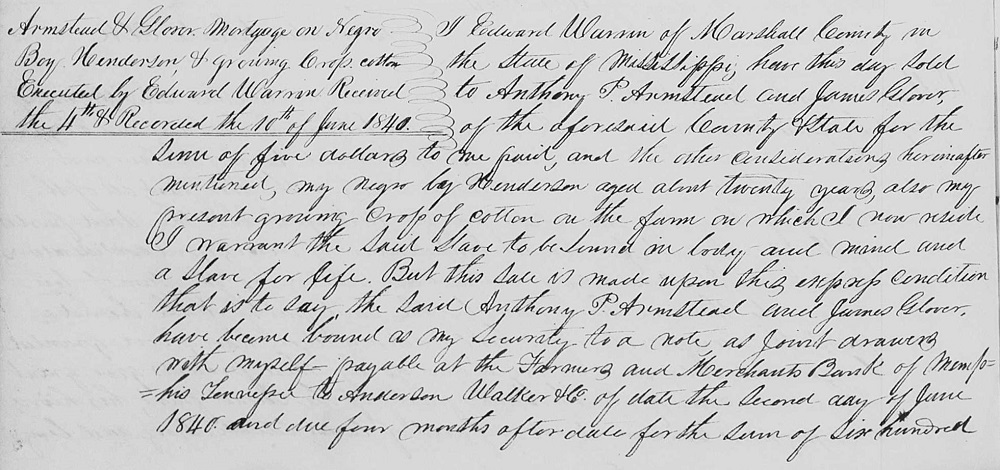

This inconsistency of maiden names led me to conduct research on white and Black families with those two surnames in Tate County and the neighboring counties of DeSoto, Marshall, and Panola for any clues. I desired to find the answer to my question – did a Briscoe or a Warren sell Grandma Peggy to Joseph Milam? I found whites with those surnames in neighboring Marshall County in the 1850 and 1860 censuses and slave schedules. I hit pay dirt in 2012, when I found the following 1839 bill of sale in the microfilmed Marshall County, Mississippi deed records at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson. Fortunately, these court records are now digitized on FamilySearch.org.

. . . the party of the first part (Edward Warren) do hereby bargain sell and confirm to the party of the second part (James W. Briscoe) all the following described property to wit: six negroes viz; ADAM aged about 55 years, SARAH aged about 40 years, JANE aged about 14 years, MARGARET aged about 10 years, CALIDONIA aged about 8 years, RANDOM aged about 23 years and one half of the growing crop of cotton in cultivation by the party of the first party . . . August 14, 1839 (partial transcription, Deed Book H, page 125, Marshall County Deed Records, 1836-1886)

Shortly after moving to Marshall County from Williamson County, Tennessee in the 1830s, Edward Warren probably incurred financial issues and thus purported to sell six enslaved people to his cousin, James W. Briscoe. I haven’t found documentation that shows that this Margaret was actually sold to Joseph Milam. However, autosomal DNA technology, more genealogy research findings, and naming patterns have collectively confirmed five things: (1) Adam and Sarah were husband and wife; (2) Random, Jane, Margaret, and Caledonia were four of their children; (3) Margaret was indeed Grandma Peggy Milam; (4) all six of them were actually never sold to or last enslaved by James W. Briscoe; and (5) Adam and Sarah had additional children.

Edward Warren died three years later in October 1842. He died intestate (without leaving a will), but I fortunately found his probate record on familysearch.org. The slave inventory in his probate record confirmed that Adam and Sarah were a married couple. Also, it included four of the six enslaved people from the 1839 bill of sale: Adam, Sarah, Random, and Caledonia. See below.

Edward Warren’s probate record also shows that the estate executor, Edward Allen Warren, who was his nephew/son-in-law, sold Adam and Sarah to his brother, B. M. Warren, aka Byrd W. M. Warren. Census records show that both brothers relocated to Ouachita County, Arkansas by 1850. Adam and Sarah probably lived their last years together near Camden, Arkansas, having seen all of their children sold away from them. The reported parents’ birthplaces in the censuses indicate that they were born in Virginia, c. 1783 and 1799, respectively. They had been brought down to Williamson County, Tennessee, then taken to Marshall County, Mississippi, and likely then taken to Ouachita County, Arkansas.

DNA Group A: Random Briscoe of Marshall County, Mississippi

I found Random again when I searched for court records (will, probate, etc.) on James W. Briscoe, to see if Random was in his possession after 1842. I couldn’t find anything on James, but his brother, Notley W. Briscoe, owned 40 slaves in 1850, per the Marshall County slave schedule. Notley died in 1860, and his will and probate record was a huge find. Random was documented in his court records; he had actually been sold to Notley!

Notley Briscoe’s plantation was located near the Waterford community, south of Holly Springs. So Random Briscoe was about 15 miles away from Grandma Peggy. Interestingly, he named two of his children Sarah Ann and Caledonia. This isn’t coincidental. I’ve theorized that perhaps Grandma Peggy got a chance to see him periodically, and thus family members may have associated the surname Briscoe as being her maiden name.

As shown in the diagram below, at least nine descendants of Random Briscoe, from four of his children, Sarah Ann, Parthenia, Rufus, and Amanda, share DNA with my mother, her brother, and/or her sister. They are COUSINS A1 – A9 below. Most of them share DNA with two of the three siblings.

DNA Group B: Jane Webster of Columbia County, Arkansas

Researching the family trees of DNA matches led me back to Jane Webster of Columbia County, Arkansas. There’s little doubt in my mind that she was likely the same 14-year-old Jane in Edward Warren’s 1839 bill of sale. Both the 1870 and 1880 censuses reported Tennessee as her birthplace. Also, according to the censuses, her older children, Henderson Ellis (c. 1848), Henry Ellis (c. 1850), Charles Ellis (c. 1850), Caledonia Ellis (c. 1852), were born in Mississippi. The rest of her children were Websters, as Jane married a man named Daniel Webster. Interestingly, she named one of her daughters Caledonia. She and Grandma Peggy both named a son Henderson. This isn’t coincidental.

I theorize that Edward Warren’s son-in-law, Erasmus J. Ellis, probably purchased Jane and brought her and her children to Arkansas. Per the 1850 census, Edward’s widow, Elizabeth Warren, age 75, lived with Erasmus and Susan (Warren) Ellis in DeSoto County, Mississippi. Land records and censuses indicate that they migrated to Ouachita County (Camden), Arkansas by 1858. After slavery, Jane and her family lived near Magnolia, Arkansas, in adjacent Columbia County.

As shown in the diagram below, at least eight descendants of Jane Webster, from five of her children, Henderson, Henry, Caledonia, Mary, and Clayton, share DNA with my mother, her brother, and/or her sister. They are COUSINS B1 – B8 below. Most of them match two of the three siblings.

DNA Group C: Henderson Herron of Tallahatchie County, Mississippi

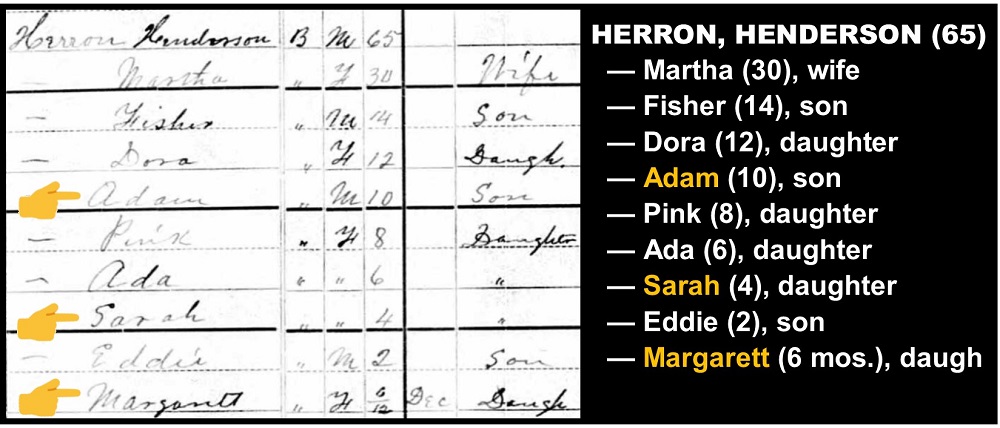

COUSIN C8, as shown in the diagram below, appeared as a DNA match in 2013. She shares 34, 72, and 76 cM with my uncle, aunt, and my mother, respectively. Mutual DNA matches indicated that she may be related via Grandma Peggy Milam. But how? I didn’t recognize the names of her grandparents, and I expanded her family tree back to her great-grandparents, Henderson & Martha Herron. They were enumerated in the 1870 census in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi and the 1880 census in Yalobusha County, Mississippi. The family resided near the town of Oakland, which sits on the Yalobusha-Tallahatchie County line. Henderson’s birthplace was reported as being Tennessee.

Initially, I had theorized that Edward Warren’s daughter, Nancy, and her husband, John Herron, had acquired and brought Henderson to Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, when they had settled there from Williamson County, Tennessee by 1836. I have since disproved this theory.

Researching the Marshall County deed records recently led me to another great find. I found a deed, dated June 10, 1840, that disclosed that Edward Warren sold a 20-year-old enslaved male named Henderson to Anthony Armstead and James Glover! See below. This 1840 deed essentially revealed that Warren had also “owned” an enslaved male named Henderson, who was not named in his 1839 bill of sale. This is the first of five pieces of evidence that Henderson was Adam and Sarah’s son. But why did Henderson take the Herron surname?

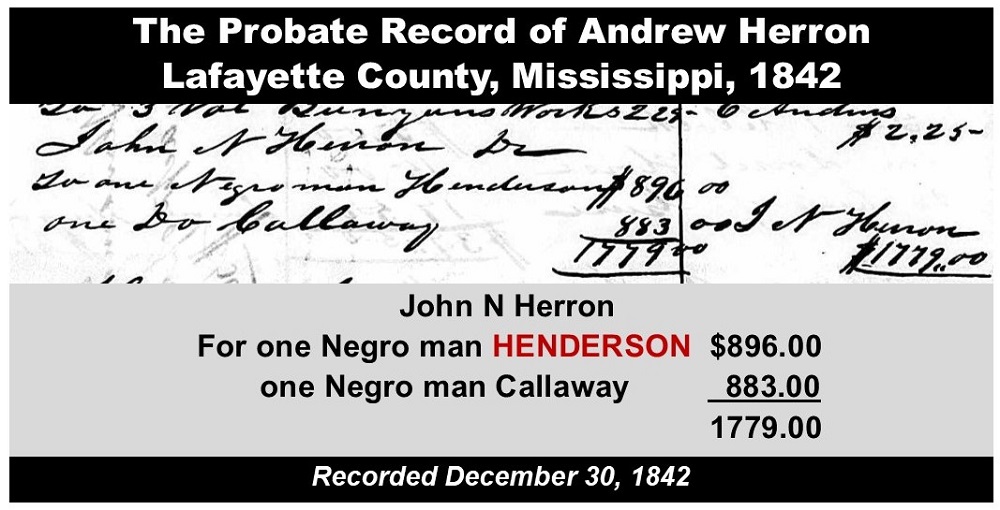

I soon discovered that Henderson was documented in the probate record of Andrew Herron of Lafayette County, Mississippi; he had died in Nov. 1842. Apparently, Anthony Armstead and James Glover decided to sell Henderson to Andrew Herron, who lived about 20 miles away in the College Hill community of Lafayette County. Perhaps, Armstead and Glover split the profits from this unfortunate sale.

Andrew Herron’s probate record shows that his son, John N. Herron, had purchased Henderson from the estate for $896 in Dec. 1842. The 1850 U.S. Federal Census shows that John N. had moved to Tallahatchie County by 1850, and the 1850 Slave Schedule reports that he had 12 slaves. This discovery is the second piece of evidence that supports my claim that Henderson was a son of Adam and Sarah.

The third piece of evidence is shown in the names that Henderson Herron gave to three of his children, namely Adam Herron, Sarah Herron, and Margaret Herron. See 1880 census below. This isn’t coincidental.

The fourth piece of evidence is the fact that Grandma Peggy and Jane Webster both gave the name “Henderson” to one of their sons. This isn’t coincidental, either.

Last but certainly not least, the fifth piece of evidence is DNA. As shown in the diagram below, at least eight descendants of Henderson Herron, from four of his children, Julia, Dora, Adam, and Eddie, share DNA with my mother, her sister, and/or her brother. They are COUSINS C1 – C8 below. Shared DNA matches include descendants of Random, Jane, and Grandma Peggy.

Their brother, Henderson, was found. After he was taken down to Tallahatchie County by 1850, a distance of around 45 miles separated him and Grandma Peggy. I can’t help but wonder if she saw him again, especially since the “ownership” of Henderson was transferred between five people, from June 1840 to December 1842. Most likely, their parents, Adam and Sarah, didn’t.

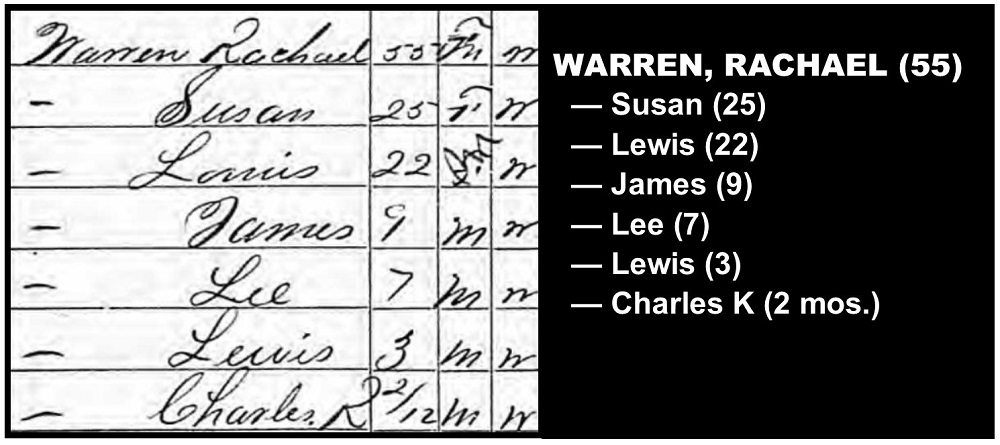

Rachael Warren of Columbia County, Arkansas

DNA is also revealing that Adam and Sarah may have had a daughter named Rachael Warren, who was born c. 1815. She was also in the 1870 and 1880 censuses in Columbia County, Arkansas. The 1870 census taker reported that she was born in Virginia, while Tennessee was recorded as the birthplace of her children, Susan Warren Cooper and Lewis Warren. In the 1880 census, Tennessee was reported as her and her children’s birthplace. In 1870, Rachael and her family lived adjacent to Daniel & Jane Webster.

One of her descendants, a 3X-great-granddaughter via her daughter Susan, share 28 cM of DNA with my mother and 19 cM of DNA with her sister. Shared DNA matches are four other descendants of Adam and Sarah. Either Rachael may have been Adam and Sarah’s daughter or the unidentified father of her daughter, Susan Warren, may have been their son, who was left back in Tennessee when Edward Warren migrated to Marshall County, Mississippi in the 1830s. More research will be done to confirm this connection.

Was There Any DNA Triangulation?

The answer to the question is YES! Fortunately, several of the 26 DNA matches in the diagrams took the 23andMe DNA test. Therefore, I was able to view the matching chromosome segments. On my mother’s chromosome 8, she matches Cousin A7, a descendant of Random Briscoe of Marshall County, Mississippi, and Cousin B3, a descendant of Jane Webster of Columbia County, Arkansas, on overlapping segments. They all match each other in this region of chromosome 8. This means that they inherited 14 cM of identical DNA on chromosome 8 from a common ancestor – Adam or Sarah.

This is amazing work, Melvin! I really need to up my game and do this to work towards finding the family of my great-grandfather, Calvin, as well as my 2x great-grandmother, Anna.

Your work is inspiring!

Renate

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is #goals! Wonderful work, Melvin!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing your diligence and excellent execution of findings. I don’t know how you find the energy but keep going!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Melvin, this is what we call having a brilliant mind. Thanks for sharing!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great research and presentation, as always, Mel!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cousin Melvin,

This is an amazing find and impeccable research. I always enjoy your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a fantastic article, Melvin. Congratulations in presenting some very complex subject matter in an easy and conversational style. That is not always an easy accomplishment.

May I ask what template or program you used to create your DNA descendency charts. I need to share some descendancy data with someone I am working with and need this very style of chart to make it clear for them.

Thank you in advance.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! I used Microsoft Word. Click “Insert” and then “Smart Art.” In the list of Smart Art graphics, select “Hierarchy” and then select the “Table Hierarchy.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Melvin, I got your website from Robyn Smith so much information you two. I have researched part of my family history back to slavery and their slaveowner trying to take it to the next level of DNA not quite to nerd my family call me lol it can be quite confusing…. Love your page especially the old pictures, please email me. Tanya

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tanya and I wish you much success with your research! If you have any DNA questions, you can e-mail me at RootsRevealed@yahoo.com.

LikeLike

Hi, Melvin, so glad I found this. Random Briscoe, Sarah and Adam Warren are my 5th great grandparents. I’ve been looking for more research about them. My family is from Marshall County, Mississippi. You’ve done such great work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Kendra, well that makes us cousins. Glad that you found this post!

LikeLike

Pingback: Ten DNA Sleuthing Tips – Roots Revealed

Hi, Melvin. This is another wonderful post! You have done excellent work piecing this family back together. Thank you for sharing! (And, I love your graphics.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Dana!!

LikeLike

Hi Melvin,

I am a part of Henderson Herron and his son Adam Herron’s extended family. Adam Herron was my great-great-grandfather. I researched and found Henderson Herron along with his mother Harriett (B. 1797) and seven brothers as part of the estate of Thomas Herron, brother of Andrew Herron, and uncle of John Herron living in Davidson County, Tennessee. When the estate was settled in 1822, and I have copies of the settlement, Henderson was awarded to Caroline Herron was the age of 5 years old as was Henderson at the time. Henderson’s other brothers and sisters as well as his mother was awarded to the various members of Thomas Herron’s family. Caroline Herron later appeared in Charleston, Miss. Her records reveal that when she died she owed her uncle Andrew Herron money. My assumption was that Henderson was given to Andrew to pay off Caroline’s debt. Thus my research is a bit different from yours regarding Henderson Herron and his Children. I have a picture of Adam Herron who moved to Kansas City, MO, and lived with his Son Henry Herron and family. He later married a second time and passed away.

The Herron enslavers moved to Davidson County, Tn in 1805. The brothers purchased land next to each other. They originally started out in Mecklenberg County, NC, later moving to Madison, Kentucky, and then to Tennessee and later Marshall County, MS. I have copies of the land purchase. Andrew Herron’s niece wrote a piece about him and his family for the Mississippi Geneology Society. I had to chance to talk to her a few times but I do not know whether she is still living. She sent me a copy of Andrew Herron’s Settlement and I found some info on his son John in the courthouse in Yalhousha county, MS. When John died, Henderson was not a part of his will nor settlement of the estate.

Please call me at 901-751-7486 when you have a moment. If I am away from my phone please leave a message and let me know a good time to return your call. My sister Linda Tolbert has also done some research on the Herron line and her number is 901-861-1178. My name is Jean Drew.

LikeLike

Hi Jean, I am aware of the Henderson you speak of, and I have seen some of the records, including the estate of Thomas Herron. Here’s the confustion: there were two Henderson Herrons. When Thomas Herron died in Williamson County, Tennessee, his widow, Mary Herron, and several of her children moved to Mississippi for a short awhile, and then she and at least two of her sons moved to Navarro County, Texas. They took their enslaved people with them to Texas, including the Henderson Herron you mentioned. That’s where I found the other Henderson Herron living in 1870, in Navarro County, TX, with his wife and children in the 1870 census. In the the 1860 census, you will find Mary Herron and her sons in that census for that county. I am 100% sure that your/our Henderson Herron of Tallahatchie County, Mississippi is the one I uncovered and provided genealogical and genetic evidence of in this blog post. No question about it. “Tallahatchie Henderson” and my 3X-great grandmother Peggy were the children of an enslaved couple named Adam and Sarah. That’s where your great-grandfather Adam’s name came from. Henderson had named 2 of his children after his parents. Additional children of Adam and Sarah ended up in Arkansas, as this blog post shows and DNA triangulation can definitely prove. If you have additional questions, feel free to e-mail me at RootsRevealed@yahoo.com.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In AncestryDNA, Linda Tolbert shares DNA with me, my mother, my aunt, as well as numerous other descendants of Henderson Herron of Tallahatchie County, Mississippi.

LikeLike

Wow this is awesome work sir. I am a descendant of Henderson Herron. I came across your page after google searching Julia Ann Herron (daughter of Henderson) and the Briscoe Family. Your page helped answer a lot of questions for me about the switch of sir name from Briscoe to Warren; why Random remained Briscoe despite grandpa Henderson taking the name Herron. It seems that the father of our grandpa Adam was a white man named Parmenus (sp) Briscoe, however, I might be wrong about his race. The research continues.

This has been very insightful.

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! By the way, Adam was born around 1783, and I haven’t uncovered anything about his parents. Can I ask why you think his father was white? If you are seeing that in others’ family trees, it didn’t come from my research.

LikeLike

Pingback: From Whom Did This Native American DNA Come From? – Roots Revealed