Juneteenth commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery in Galveston, Texas on 19 June 1865. The Emancipation Proclamation, that had an effective date of 1 January 1863, did not immediately emancipate most enslaved African Americans in the South, especially in Texas. On that day, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger read General Order #3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

General Order No. 3, from the holdings of the US National Archives and Records Administration. Citation: RG 393, Part II, Entry 5543, District of Texas, General Orders Issued

Coined “Juneteenth,” June 19th soon evolved into a national celebration of the emancipation from American chattel slavery. On 17 June 2021, Pres. Joe Biden officially made Juneteenth a federal holiday. I often wonder about the day my enslaved ancestors were told that they were free. How did they feel? What did they do? Did they cry a river of tears? Did they dance with joy? The day they were notified of their freedom was undoubtedly a dream come true. However, they also had to answer the question, “What do we do now?”

Since the 26 May airing of the excellent Netflix series, High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America, I have been thinking a lot about the life of my mother’s great-grandmother, Polly Partee of Panola County, Mississippi. The series beautifully illuminated the history of American foods, from West Africa to America, masterfully interweaving many aspects of African American history and culture in American cuisine. Grandma Polly was said to have been the enslaved head cook on Squire Boone Partee’s plantation during and after slavery. In the late 1990s, a family elder even shared this account with me, “Momma (Martha Reed Deberry) often talked about how Grandma Polly was such a great cook, that the food you didn’t like tasted delicious!” I learned more about Grandma Polly’s role and experiences from watching this series.

When Grandma Polly heard the words, “You a free woman now,” she decided to stay on the Partee plantation with her four young children (Sarah, Judge, Square, & Johnny Partee), as evidenced by the 1870 and 1880 censuses. In 1870, her adjacent neighbor was Squire Partee’s widow, Martha Douglass Partee. In 1880, her adjacent neighbor was Squire & Martha Partee’s son, Charles Watkins Partee. See image below.

According to the censuses, Grandma Polly was born somewhere in North Carolina, probably around 1830. I ascertained that she had been sold away and somehow became enslaved by Squire Partee by 1852, the year her oldest child, Sarah Partee Reed, my mother’s paternal grandmother, was born in Panola County. Over the past two decades, I have not found any documental clues about her origins in North Carolina, her family, and the circumstances of how she became enslaved by Squire. He had moved to northern Mississippi in the 1830s from Henry County, Tennessee. I have pondered if Squire purchased Grandma Polly off an auction block because nothing has been found to date that ties her to Squire’s family, as well as Squire’s wife’s family. She has been one of my hardest research cases. I have not even found an associated maiden name for her. Other than her children, family elders did not know of any people in the area that were related to her. However, DNA technology has uncovered something!

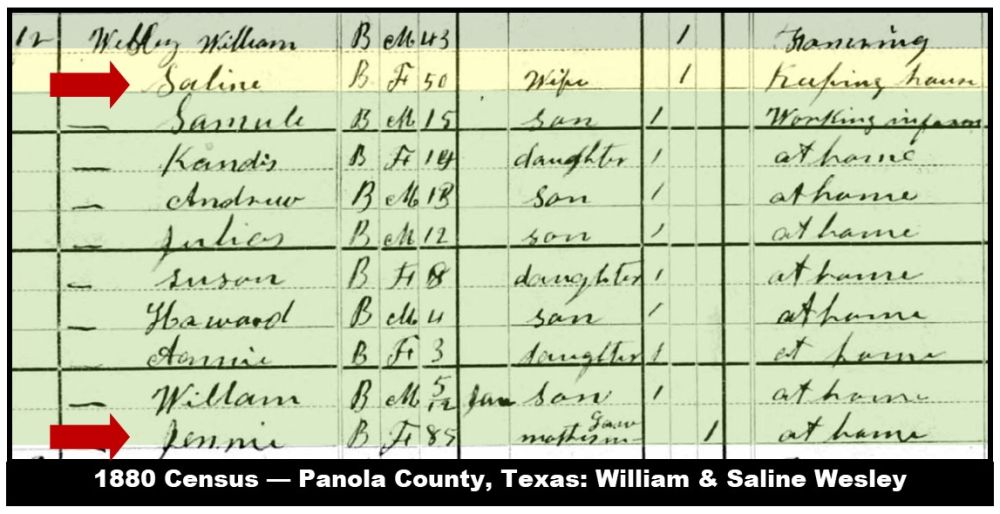

Studying the family trees of DNA matches in AncestryDNA and 23andMe, I discovered that my mother, aunt, uncle, and their paternal first cousin – Grandma Polly’s great-grandchildren – share sizable amounts of DNA with at least nine descendants of William & Saline Wesley of Panola County, Texas. Yes, another Panola County! See diagram below. To date, the highest DNA amount is 125 cM over 7 segments with a great-great-granddaughter in Texas (Cousin 3). Who are the Wesleys?

Per the 1870 and 1880 censuses, William Wesley was born in Tennessee. Someone told the 1880 census-taker that Saline was born in Mississippi and that both of her parents were born in North Carolina. Not only that, the mother-in-law, Jennie, was in their household in 1880. Her reported age was 85, and her reported birthplace was North Carolina. Although this suggests that Jennie was the mother of Saline, what if the informant was Saline, and she told the census-taker that Jennie was her mother-in-law? Hmmmm….. See image below.

Although the DNA numbers (cM) strongly suggest that William or Saline may have been Grandma Polly’s sibling, more research is being conducted to try to confirm the family relationships. Undoubtedly, the family kinship was close. William or Saline or Jennie were probably family members that Grandma Polly thought of when she heard the words, “You a free woman now.” Perhaps, she wondered about their whereabouts and the whereabouts of other family members. DNA is also linking her to Black families in Wake and Granville County, North Carolina.

Grandma Polly considered that her best option was to just stay put in Panola County, Mississippi, continue raising her children, and continue to cook for the white Partee family as late as 1880. Perhaps, the white Partees encouraged her to remain on the plantation so they could continue to enjoy her great cooking. Hopefully, they paid her. Oral history, autosomal DNA, and Y-DNA have pinpointed a man named Prince Edwards as the father of her children. He had been enslaved nearby on William Edwards’ farm. He chose another woman, Leanna, as his spouse and had eight additional children. So, Grandma Polly was the head of her household and made the best of her new, great reality – freedom. Happy Juneteenth!

Great article (as always), Melvin!

Granville County is in my research area. I(It was part of Edgecombe County before 1746.) I’d love to know which surnames you’re matching from there.

Thanks for sharing!

Renate

LikeLike

Bullock, primarily, and the county is full of them, both black and white! 😦

LikeLike

Good morning Melvin, this is Lester A. Lowe of Fayetteville,NC distant Cousin. I’m looking forward to learning more through rootsrevealed & ancestry 🗣🙏🏽🙌🏽💯

LikeLike

Wow! Now your in my neck of the woods. My maternal-grandfather’s family was from Panola County, Texas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mother Wit

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: These Findings Can’t Be Coincidental – Roots Revealed