When we research our enslaved ancestors, we must consider several different scenarios concerning family relationships. Our ancestors were considered “property,” and many enslaved men were forced to procreate with other women to increase an enslaver’s wealth. Breeding occurred on many farms and plantations. Also, many enslaved women were required to bear as many children as they could. When these inhumane scenarios occurred, it created complex family structures that can be cumbersome to figure out genealogically. It also produces a lot of DNA cousins.

For example, in the 1870 DeSoto (now Tate) County, Mississippi census, I found my mother’s great-great-grandfather, Wade Milam, heading a household that contained his wife Fanny and their five children. Wade is also the confirmed father of most of my 3X-great-grandmother Peggy Milam’s children. Wade and Peggy had both been enslaved on Joseph R. Milam’s farm.

Peggy and her children resided in a separate household in 1870, not far away. Some of the children that Wade fathered with his wife Fanny, who was presumably on a different farm during slavery, were born around the same time as some of Peggy’s children. Based on oral history and an obituary of Wade’s son with his wife Fanny, both sets of his children knew each other.

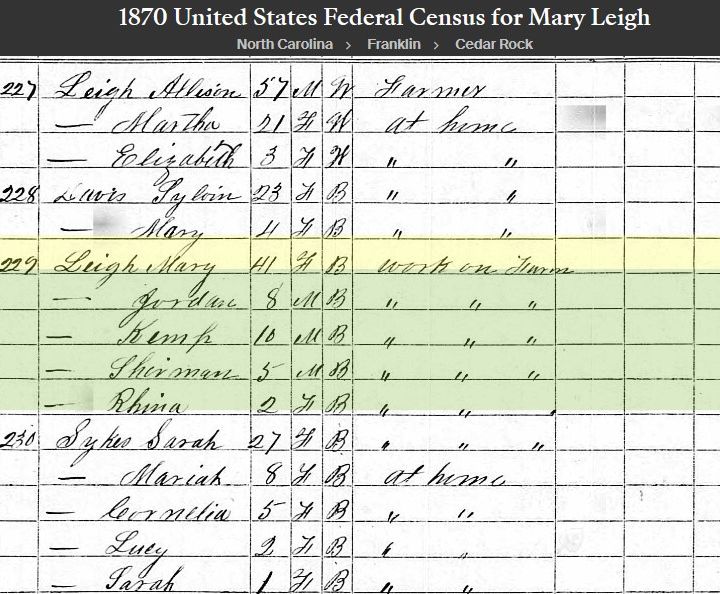

Let’s look at the case of Cary Stokes of Franklin County, North Carolina. DNA matches to my father led me to this case. Both Cary Stokes and Mary Lee (Leigh), the mother of some of his children, had been enslaved by William Stokes up until his demise in 1854. In William Stokes’s estate file below, Cary, Mary and three of her children, Adaline, Sarah, and Harry, are highlighted. He was the only Cary documented in this estate file. Marriage records and death certificates reported him as the father of at least four of her children, including Sarah and Harry.

After William Stokes’s death, his daughter Nancy, who married Allison Leigh, inherited Mary and her children. In the 1870 census, Mary lived next door to widower Allison Leigh, and she and most of her children also took the Leigh surname, which was eventually spelled as “Lee.” Her daughter, Sarah Sykes, and her children also lived next door.

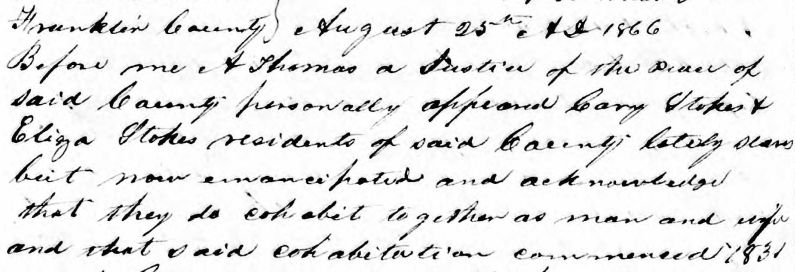

However, this 1866 North Carolina cohabitation record below shows that Cary Stokes and a woman named Eliza Stokes had been husband and wife since 1831.

Per William Stokes’s estate file, Eliza and her children had also been enslaved by him, and his son, Grey W. Stokes, inherited them. Eliza and some of her children were found living near Mary and her children, per the 1870 census of Franklin County, North Carolina. Cary appeared to have died shortly before 1870. Next door to Eliza was their last enslaver, Grey W. Stokes.

So, in the research of our enslaved male ancestors, we must consider that some of them may have been forced to father additional children outside of their permitted marriages. We also must take this scenario into consideration when trying to figure out how some of our DNA matches may be related.

My father’s great-grandfather, Robert “Big Bob” Ealy of Leake County, Mississippi, who was born in nearby Nash County, North Carolina c. 1819, was somehow related to Cary Stokes or Mary Lee. My father and some of his Ealy cousins share DNA with over 15 descendants of Mary Lee, and not to any of Eliza’s descendants thus far, so the connection appears to point to Mary.

Similarly, Big Bob Ealy had also been forced to father children outside of his permitted marriage to his wife, my great-great-grandmother Jane Parrott, who had been enslaved on Rev. William Parrott’s farm nearby. My late grandmother had relayed Big Bob’s story to me when I was 15.