Recently, an eye-opening DNA cousin appeared among my mother’s matches on Ancestry.com. She shares 23 cM with my mother and shares even more DNA with my mother’s sister and brother – 36 cM and 43 cM, respectively. These are not insignificant amounts of shared DNA, giving me confidence that I could potentially determine how she connects to our family.

When I examined the shared matches with this new cousin, I noticed that this same cousin also shares 25 cM with two of my mother’s second cousins. That strongly suggested that she is connected to one of my mother’s great-grandparents, either Edward Danner or his wife, Louisa Bobo Danner, both born in Union County, South Carolina. They were transported to Panola County, Mississippi by their enslaver, Dr. William Bobo, before 1860. None of Louisa’s known sibling descendants appeared among the shared matches, which led me to theorize that the connection was probably through Edward Danner.

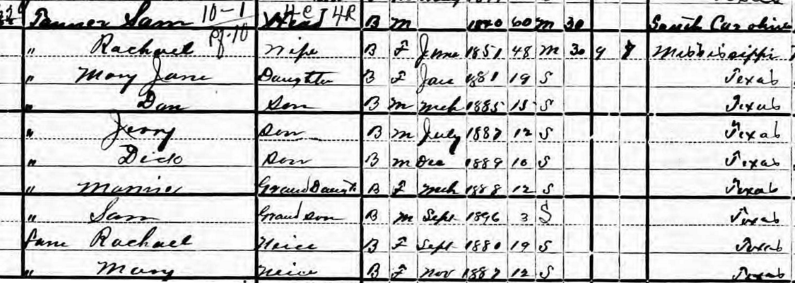

Fortunately, this DNA cousin has a public family tree. As I reviewed it, I noticed that both sides of her family were rooted in Texas. But one detail immediately caught my attention: her great-grandfather was Samuel Tanner, consistently recorded as being born in South Carolina around 1840 in the 1880, 1900, 1910, and 1920 censuses of San Augustine County, Texas. His surname Tanner raised eyebrows. Unfortunately, his son, Richard “Dick” Tanner, the informant of his 1921 death certificate, did not know the names of his parents.

My great-great-grandfather, Edward Danner, was born c. 1835, and he and his parents had been enslaved by Thomas Danner Jr. in Union County. The surnames Danner and Tanner were often used interchangeably in historical records. In fact, Edward himself was recorded as “Tarner” (or Turner) in the 1870 census of Panola County, Mississippi. In a previous blog post, I discussed how the daughter of Edward’s proposed sister, Matilda Beaty of Union County, had reported her maiden name as either Tanner or Danner. This pattern of surname variation could not be ignored.

Further DNA sleuthing revealed that my family also shares DNA with at least six other descendants of Samuel Tanner through three of his ten children. This additional genetic evidence strengthened the likelihood that our connection was indeed through Samuel. The pressing questions then became: How did Samuel end up in San Augustine, Texas? Was he originally from Union County, South Carolina? And how might he have been related to Edward Danner?

Thomas Danner Jr. died in 1855 in Union County, but his estate records do not contain a slave inventory. By 1860, his widow Nancy and their children had relocated to Saline County, Arkansas, taking with them only an enslaved woman named Harriet Danner and her seven children. No migration to Texas was documented among this branch.

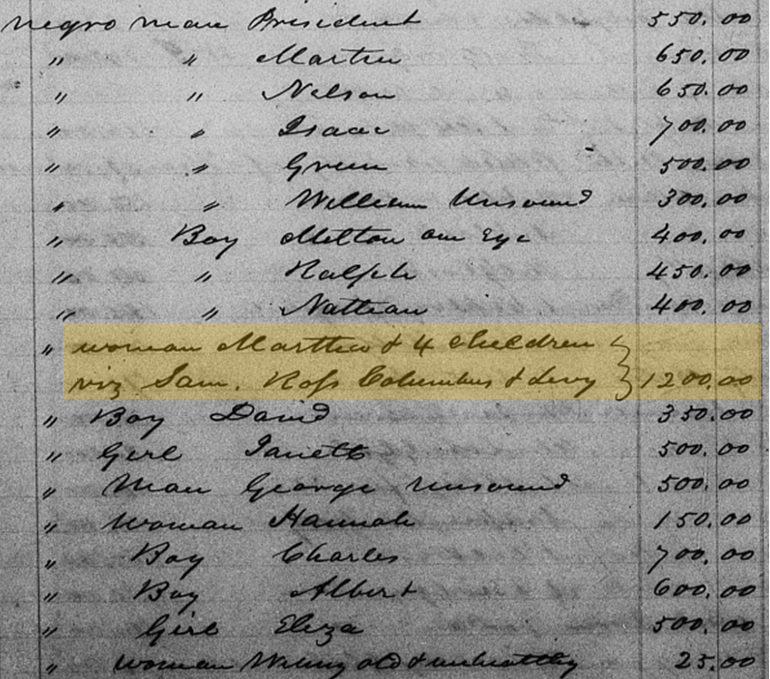

However, the earlier generation provided a clue. Thomas Danner Sr., who died in 1844, left an estate that included a slave inventory taken of January 1, 1845. Among the twenty-two enslaved individuals listed was “Negro woman Martha and 4 children, Sam, Ross, Columbus & Levy,” collectively valued at $1,200. See below. Interestingly, Samuel Tanner’s first-born daughter was named Martha. Was this coincidence? Was this evidence that Samuel Tanner was the “Sam” listed in the 1845 inventory? I needed more.

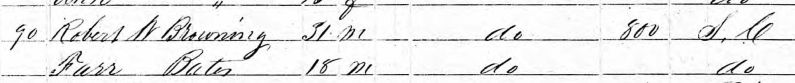

While reviewing David Getzendanner’s book, Thomas Getzendanner of Maryland and South Carolina, I encountered a significant lead. Thomas Danner Sr.’s eldest daughter, Catherine Danner, married a third time to Robert W. Browning in 1849. Shortly after their wedding, they departed for Texas. Catherine’s sons, Farr and Thomas Bates, preceded them by several days, reportedly in charge of wagons, cattle, and enslaved people. Tragically, Catherine fell ill with cholera and died near the Mississippi River at Rodney, Mississippi, before reaching Texas. The book does not specify their destination within Texas, and no other members of the Danner family are known to have migrated there during slavery. [1]

Fortunately, I found Robert Browning in the 1850 census in Texas. He resided in San Augustine County, Texas—the very county where Samuel Tanner lived. Bingo! Browning’s household included only his 18-year-old stepson, Farr Bates. See below. The slave schedules show that Browning had six enslaved people in 1850 and seven in 1860. He died in 1866, after emancipation, leaving no slave inventory to confirm whether one of those enslaved males was named Samuel. Farr and Thomas Bates had returned to South Carolina in the 1850s.

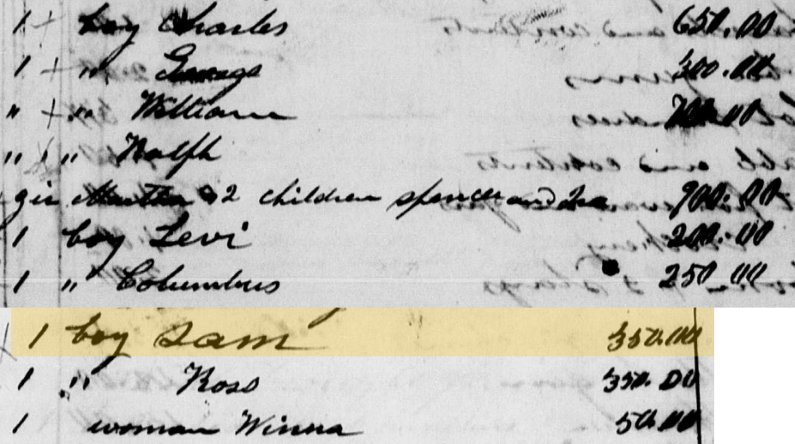

Additional estate records reveal that Thomas Danner Sr.’s widow, Amelia, inherited Martha and her four sons in 1844. After Amelia’s death in 1848, another slave inventory, dated February 4, 1849, listed Martha with two additional young children, Spencer and Joe(?), valued together at $900, and her sons Levi, Columbus, Sam, and Ross valued separately. See below. Robert Browning and Catherine’s sons, Farr and Thomas Bates, were among those entitled to an equal share of Amelia’s estate.

Although the records do not specify who ultimately inherited Martha and her children, the cumulative evidence presents a compelling scenario: Martha’s son Sam may well have been transported to Texas with Robert Browning and the Bates sons around 1849 and later became known as Samuel Tanner of San Augustine County.

Thomas Danner Jr. lived near his parents and was recorded as owning eighteen enslaved people in 1850, including Edward Danner. Some descendants theorize that Thomas Jr. resided on his father’s 1,000-acre plantation along the Enoree River in Union County. If so, Sam and Edward lived in close proximity and likely had grown up together before Sam’s forced relocation to Texas around 1849.

DNA evidence confirms a familial relationship between Samuel Tanner and Edward Danner. Based on the amount of shared DNA and additional observations, they may have been half-brothers or first cousins. A full-sibling relationship is less likely since Edward was never enslaved by Thomas Danner Sr. While further documentation and genetic evidence are needed, this case illustrates how DNA and genealogy can converge to reconnect families separated by slavery.

Even if every detail is not yet fully resolved, documenting Samuel Tanner as a relative of Edward Danner represents another meaningful step in restoring his fractured family history in South Carolina.

Source:

[1] David Cramer Getzendanner, Thomas Getzendanner of Maryland and South Carolina (Salem, OR: Published by the author, 1993), 130–137.