A common conversation in the genealogy community is how often emancipated African Americans retained the surname of their last enslavers. Varying statistics suggest that most did not, while many did. For many (or a large majority of) researchers who have ancestors who chose a different surname during or after slavery, unearthing why those ancestors chose that surname can be quite a task. Even finding the names of last and former enslavers can be quite challenging, too.

Frankly, slave ancestral research is not easy, and it is certainly not a straightforward process. It involves a lot of detective research in a number of sources or records. It took over twenty years to put a crack in this brick wall involving my 3X-great grandfather, Jack Davis, Sr. of Panola County, Mississippi. Cluster genealogy, additional slave ancestral research, and DNA all played a major role in finding five significant puzzle pieces to the large mystery puzzle of why he selected Davis as his surname. Many often selected the surname of a previous enslaver.

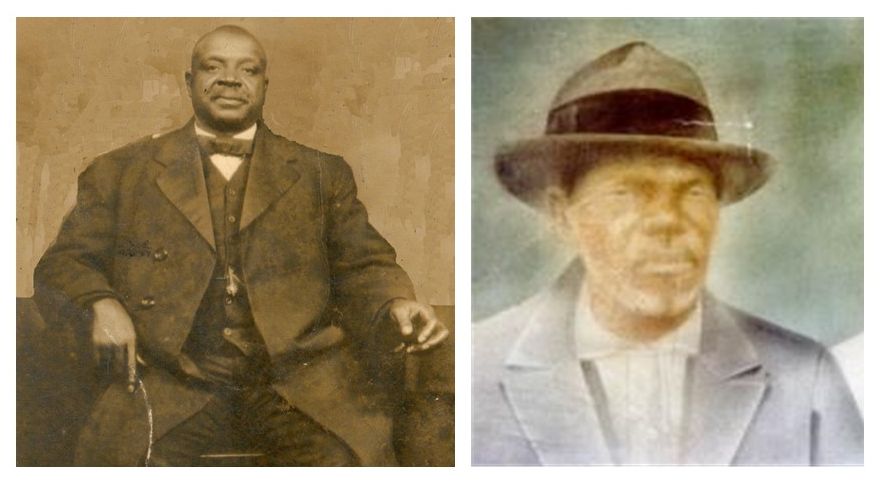

The men above are my mother’s maternal grandfather, John Hector Davis (1871-1935), and her great-grandfather, Hector Davis (1842-1925), both of Panola County (Como), Mississippi. Back in the 1990s, census records and death certificates at the Mississippi Dept. of Archives helped me to identify Grandpa Hector’s parents, Jack & Flora Davis. I even broke down that “1870 Brick Wall” after I found Grandpa Hector’s 1866 marriage record, and his surname was recorded as Burnett. Jack, Flora, and their children had been enslaved by John J. Burnett, who brought them to northern Mississippi around 1861 from the Smithville area of eastern Abbeville County, South Carolina. Burnett died two years later.

Puzzle Piece 1: The “Neighborhood” of John Burnett, 1850, Abbeville County, South Carolina

Grandpa Jack Davis was born around the early 1800s (c. 1805-12) in South Carolina. The 1850 and 1860 Abbeville County slave schedules indicate that John Burnett did not own an enslaved adult man during those times. He owned two adult females, Grandma Flora, her sister Nellie, and their children. Burnett seemed to have acquired Grandpa Jack shortly before their migration to northern Mississippi.

So, who was Grandpa Jack Davis’s former enslaver? I could not find the answer to that question from Abbeville County court records, so I employed the cluster genealogy method for clues. Cluster genealogy is the diligent act of researching a person’s friends, associates, and neighbors, aka FAN Club, to garner clues and to learn more about that person’s history.

Looking at John Burnett’s neighbors in the 1850 Abbeville County census, I found a potential clue. Burnett was recorded on page 109B in dwelling house no. 1692. Living nearby, a farmer named Ephraim Davis was recorded on the next page (p. 110A) in dwelling house no. 1701. Was he Grandpa Jack’s former enslaver? My 3X-great grandpa would have been in close proximity to his wife and children.

The 1850 Abbeville County slave schedule shows that Ephraim owned five enslaved people: (1) a 35-year-old male, (2) a 32-year-old male, (3) a 33-year-old female, (4) a 19-year-old female, and (5) a 1-month-old male. The 35-year-old male “kinda” matches Grandpa Jack, although I believe that he was around 40, plus or minus a few years. I soon discovered that Ephraim died in 1857. His probate record contained an inventory, taken Dec. 1857, which included eight enslaved people: Ginsy, Sarah and unnamed child, Jim, Warren, Eliza Ann, Mary, and George. No Jack! So, what do I do now?

Puzzle Piece 2: The Family Tree of Ephraim Davis

I investigated the family tree of Ephraim Davis for possibilities. Did he have other family in the area? The answer was “Yes.” Fortunately, I soon learned that he had a brother, Joseph Davis, who died in Abbeville County in April 1840.

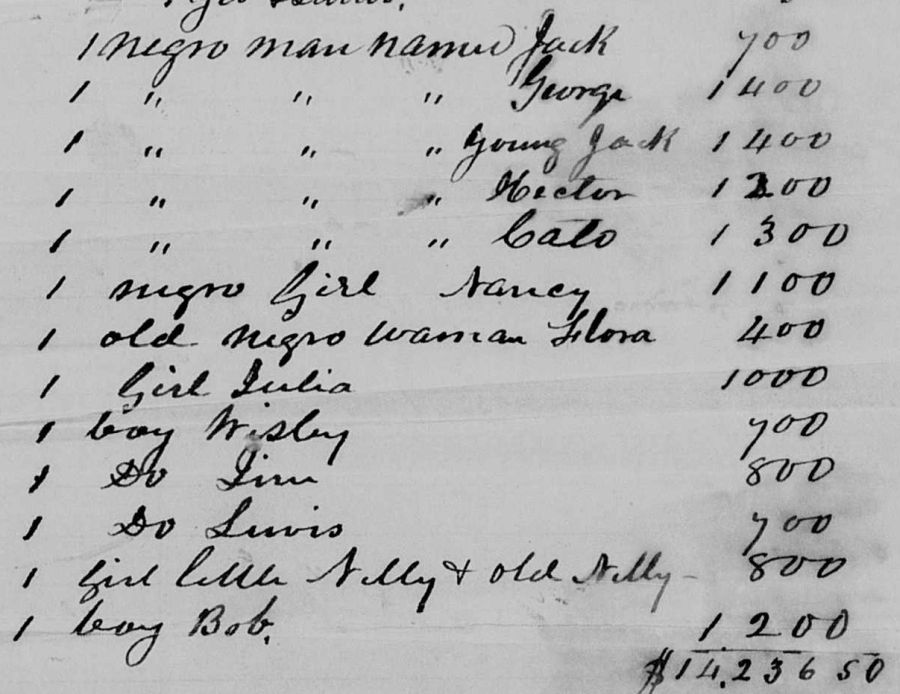

Researching Joseph Davis’s probate record was a great move! The slave inventory, taken May 1840, named 26 enslaved people. The first one on the list was “Negro man named Jack”! See figure below. Recorded transactions in the probate record indicate that Jack was sold to a man named John White, who also lived in Abbeville County. This finding looked very promising. Thankfully, more clues soon came to light by way of DNA.

Puzzle Piece 3: A Revealing Genetic Group – Descendants of Madison & Jennie Hunter

At least six DNA cousins, with close family ties to Union County, South Carolina, appeared to be related to my mother’s Davis line. See diagram below. Whenever I clicked on “Shared Matches” in AncestryDNA for those DNA cousins, other descendants of Jack & Flora appeared in the list. This baffled me for a while because my mother’s maternal grandmother’s parents, Edward Danner and Louisa Bobo Danner, were born in Union County, and their enslaver, Dr. William Bobo, took them to Panola County, Mississippi in 1858. So, when a strong DNA match is from or has close ties to Union County, I had immediately assumed they are related somehow via Edward or Louisa. How could some of my Union County DNA cousins be connected to my mother’s Davis line?

I discovered another clue. Online family trees on Ancestry.com identified Ephraim and Joseph Davis as being the sons of Capt. Nathaniel Davis who had died in Union County in 1797. Ephraim and Joseph were actually born in Union County. They had moved about 60 miles to the Smithville area of Abbeville District by 1820. Perhaps, this is why my mother, aunt, and uncle are getting strong, Davis-related DNA matches from Union County, too.

After painstakingly researching the family trees of those six DNA cousins, I found their common ancestor. I say “painstakingly” because I had to take their family trees back further, with most of them having the same surnames multiple times in their family trees. This was time-consuming and hair-pulling but perseverance prevailed. Their common ancestor was a couple named Madison & Jennie Hunter. Per the 1870 Union County census, they were both born c. 1810 in South Carolina.

Fortunately, Cousin F also took the MyHeritage DNA test, which means that I had some chromosome data. Yeah! Unfortunately, AncestryDNA does not provide chromosome data or a chromosome browser. Cousin F shares 28 cM with my mother on chromosome 16. I uploaded the chromosome data to DNA Painter, a chromosome mapping tool, and verified that the family connection is indeed on my mother’s Davis line. Everyone overlapping (triangulating) in that region of my mother’s maternal chromosome 16 all descend from Jack & Flora Davis. See figure below.

Puzzle Piece 4: Finding the Slave-owner of Madison and Jennie, Union County, South Carolina

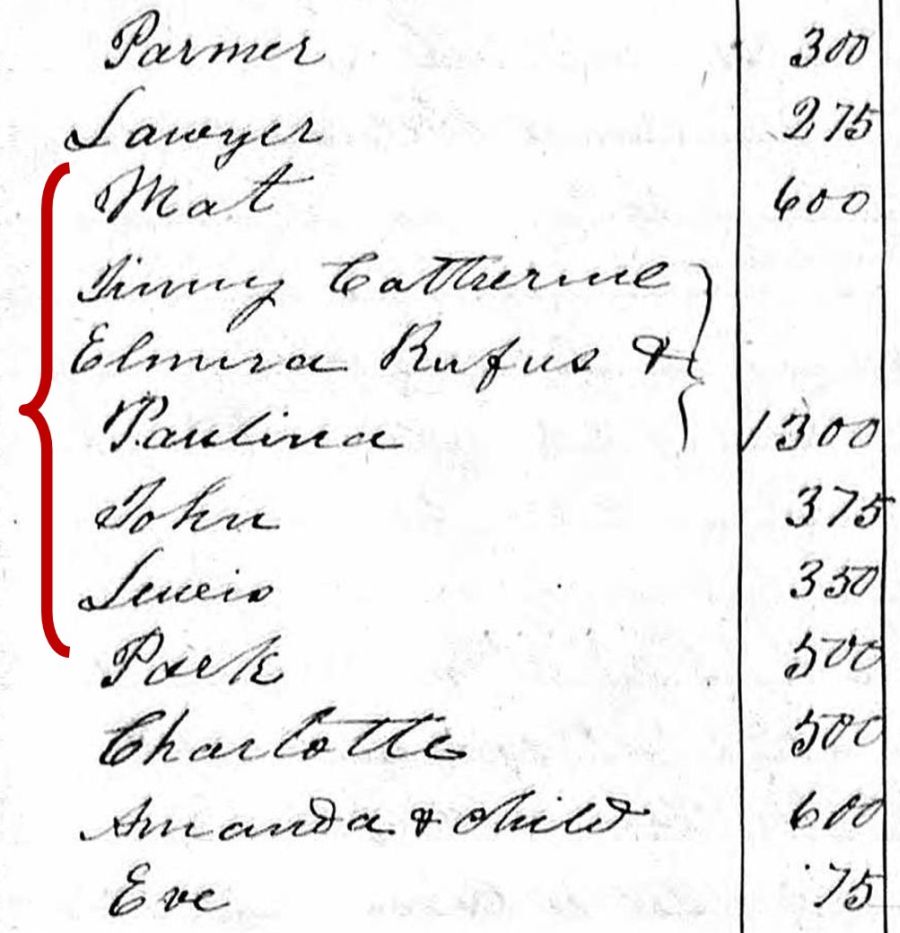

In order to find more clues, I decided to hunt for their last enslaver(s). Again, I employed the cluster genealogy method. Madison & Jennie Hunter were recorded on page 480A of the 1870 Union County census. Investigating their neighborhood, I found a 44-year-old white man named James George Washington Hunter recorded on page 480B. More research revealed that he was the son of Capt. James Hunter (1778-1846), who had emigrated to America from Ireland. Per the 1840 census, Capt. Hunter was the only slave-owning Hunter in Union County that year; he owned 28 enslaved people. Madison “Mat”, Jennie, and their children were among the 55 enslaved people who were appraised as part of his estate. But is there a Davis connection?

Puzzle Piece 5: The Probate Record of Capt. Nathaniel Davis, Union County, South Carolina, 1797

Joseph Davis of Abbeville County was the son of Capt. Nathaniel Davis of Union County who died in 1797, so I questioned if his will and probate record would provide some type of clue. Luckily, it did.

Nathaniel named seven enslaved people in his 1797 will, and nine enslaved people were inventoried with his estate. While reading the transactions of his estate, I came across an 1806 transaction that stated, “Amt paid James Hunter who has intermarried with Sarah Davis, a legatee…” See below. This was Capt. James Hunter, and he and Nathaniel’s daughter, Sarah, his first wife, had married in 1804. She also had inherited an enslaved girl named Phyllis, per Nathaniel’s will. Sarah Davis Hunter had died in 1824.

So far, any purchases or transferences of enslaved people, which may have occurred between Capt. Nathaniel Davis’s son Joseph and Capt. James Hunter, have not been found. The research continues; the puzzle is not complete. More answers are sought, such as who were or could have been the parent(s) of Grandpa Jack Davis and Madison & Jennie Hunter. Slave ancestral research definitely entails asking yourself questions from the uncovered information at hand, and then doing more research to try to find the answers.

DNA suggests that Madison or Jennie could have been Grandpa Jack’s sibling. Was Sarah Davis Hunter’s 1797 inheritance – a Negro girl named Phyllis – the mother? Was Joseph Davis’s 1797 inheritance – a Negro girl named Jane – the mother? Did Capt. Hunter purchase any other enslaved people from one of Nathaniel’s children, his in-laws? Census records revealed that he went from 6 enslaved people in 1820 to 23 enslaved people in 1830. Looks like he was expanding his plantation to include more enslaved labor. Regardless of the unanswered questions, these five puzzle pieces have been the biggest clues I have uncovered in over two decades. I am “over the moon” happy. Never give up!

What an enjoyment and enlightening experience to read your work! Thanks for sharing. It keep me going

LikeLiked by 1 person