Very often, especially with enslaved ancestral research, direct evidence cannot be found to answer a common question, “Who were his parents?” Direct evidence is documentation that clearly states the relationship between two people. However, indirect evidence, combined with other findings, can shine a light on the answer or the likely answer. This was the situation in determining the identity of a 3X-great grandmother named Lucy.

Clues from oral history, in conjunction with autosomal DNA and ultimately Y-DNA technology, uncovered that the long-sought father of my mother’s paternal grandmother, Sarah Partee Reed (1852-1923), and her brothers, Judge, Square, and Johnny Partee, was a man named Prince Edwards. He had fathered children with my mother’s great-grandmother, Polly Partee; she and her four children had been enslaved by Squire Boone Partee of Panola County, Mississippi. Grandma Polly was known to have been the head cook on Partee’s plantation during and after slavery. To add, Partee was the former son-in-law of William Edwards, Sr., who had enslaved Grandpa Prince and whose farm was nearby. After slavery, Polly and her children retained the Partee surname.

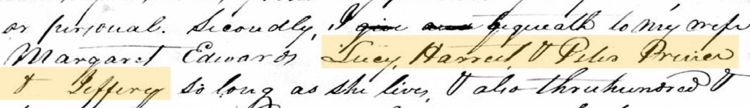

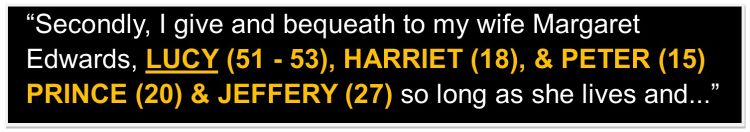

Prince Edwards was found among the 33 enslaved people inventoried in William Edwards’s probate record. He died October 2, 1855, in Panola County. However, five years before his death, Edwards wrote his will that only named five enslaved people he bequeathed to his wife. On November 14, 1850, he wrote the following:

Autosomal and Y-DNA testing evidenced that Prince and Peter were full brothers. Interestingly, Prince and Peter even gave the name Jeffery to one of their sons. To add, Peter gave the name Lucy to one of his three daughters. After slavery, Prince married another woman, and their first daughter was named Harriet aka Aunt Hattie. So, was Lucy closely connected to Prince and Peter? Was this one family that William left to his wife?

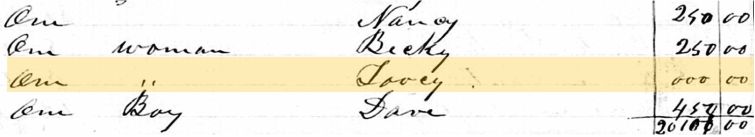

As mentioned earlier, William Edwards’s probate record contained a slave inventory dated December 15, 1855. Lucy was given a value of zero. Sadly, this meant that she was likely of an advanced age (or elderly) and was of no value.

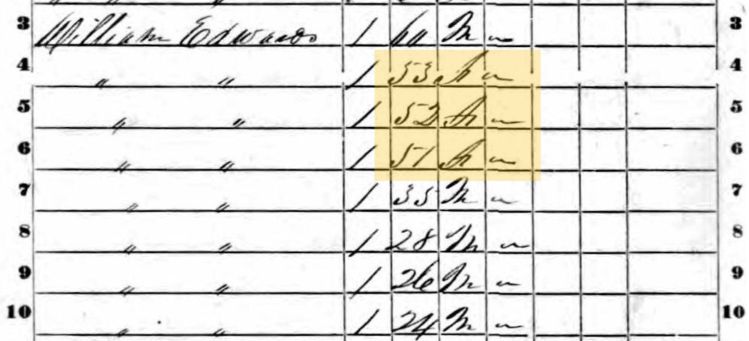

I then looked at the 1850 slave schedule of William Edwards to ascertain the recorded ages of his oldest enslaved women. Without giving names, most slave schedules only provide the age, sex, and color of a person’s enslaved people/person. This “slave census” was recorded on October 3, 1850, a month and 11 days before he wrote his will.

Per this 1850 slave schedule, the three oldest enslaved females were reported as being 51, 52, and 53. Because no names were given, I can only speculate that Lucy was likely one of the three, and that she was born around 1797 – 1799. Luckily, Harriet, Peter, Prince, and Jeffery survived slavery and were found in the 1870 and 1880 Panola County, Mississippi censuses. This allowed me to ascertain their approximate ages in 1850, when Edwards wrote his will. See the graphic below.

I theorize that William Edwards’s selection of these five enslaved people to specifically go to his wife was not a random selection or his selection based on value, but it more rather represented a woman of an advanced age and her children. Lucy was not found in the 1870 census, so one can surmise that she likely died before 1870. No records, or direct evidence, have been found to date that specifically document (or confirm) the name of Harriet, Prince, Peter and Jeffery’s mother. However, given the pieces of indirect evidence, one can plausibly assert, with a high degree of certainty, that Lucy was their mother and thus my 3X-great grandmother.

DNA is strongly indicating that she was originally from an area in or near Pittsylvania County, Virginia. Read “From Mississippi to the Upper South: DNA was the “North Star”.

Hey Melvin. I always enjoy and learn from reading your blogs. I appreciate your methodology in tracing these clues. I have always assumed that the slavery-era family groups were parents and children, especially if I find the family group with consistent ages in more than 1 record, but I will be more cautious of that in the future. Did the 1860 SS have any new clues for you? Take care my brother!

LikeLike

Thanks, Alvin. I refrained from using the 1860 SS with this case. William Edwards Sr. had died in 1855, and although all of the enslaved people went to William Jr., and Jr. was in the 1860 SS with a number of enslaved people, I felt less confident hypothesizing that all of them were from his father.

LikeLike

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - August 19, 2023 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Pingback: From Mississippi to the Upper South: DNA was the “North Star” – Roots Revealed