“Brick wall” is a metaphor used in genealogical and historical research when one reaches a point in their research where he/she is unable to progress further or “dig deeper.” All researchers encounter it. For those tracing African American ancestors, this proverbial brick wall is commonly encountered at the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, a vitally important census particularly for African American research.

I have written about and given presentations on numerous genealogical cases in which cluster genealogy played a major role in breaking down that 1870 brick wall. Cluster genealogy is the diligent act of researching a person’s friends, associates, and neighbors, aka FAN Club, to garner clues and to learn more about that person’s history, as well as possibly finding the last enslaver. There’s no doubt that it’s one of the most effective methodologies for enslaved ancestral research. Here’s another example.

In AncestryDNA, I discovered that my father shares DNA with at least ten descendants of a woman named Minerva Winfield of Brunswick County, Virginia. These ten DNA cousins descend from six of her children, and they share from 11 to 50 cM, which captured my attention.

Born c. 1805-10, Minerva Winfield had at least nine children: Jack Winfield, Osborne Winfield, Lucretia Winfield Fields, Alfred Winfield, Eady Winfield Chambliss, Nancy Winfield Mitchell, Richard Winfield, Edward “Ned” Winfield, and Anderson Brown, Jr. Virginia marriage records and death certificates on Ancestry.com revealed that the father of most of them was named Daniel Winfield, while several of them were fathered by men named Richard “Dick” Winfield and Anderson Brown. Because all her children didn’t appear to have the same father, this helped to pinpoint my family’s DNA connection directly to Minerva.

Shared DNA matches in Ancestry.com indicate that Minerva Winfield was related to my father’s great-grandmother, Jane Parrott Ealy of Leake County, Mississippi; she had been born in Virginia c. 1829. Grandma Jane, her mother, also named Minerva, and her siblings had been enslaved by Rev. William Parrott, who brought them to Mississippi shortly before 1840 from Lunenburg County, Virginia. Genealogy research has uncovered that Jane’s mother Minerva, born c. 1811, was obtained from the estate of William Parrott’s father-in-law, Julius Johnson of Brunswick County, Virginia, in 1824.

Going back further, Jane’s mother Minerva was an inheritance to Julius Johnson from his father Benjamin Johnson, also of Brunswick County, Virginia. He wrote in his 5 December 1812 will, “I give unto my son Julius Johnson, one Negro man Tom which he has in his possession also one Negro woman Rachel and her child Manerva to him and his heirs forever.”[1] Per Benjamin Johnson’s August 1813 estate inventory, he also owned an elder woman, also named Manerva, who was valued at $100. [2] One can plausibly assert that this elder Manerva in 1812 was most probably the mother of Grandma Jane’s grandmother Rachel and was my father’s 4th-great-grandmother.

Somehow, Minerva Winfield was connected. Determining the “how” would be difficult, but I first wanted to know who had enslaved Minerva Winfield and her children. Maybe this would help to solve this mystery.

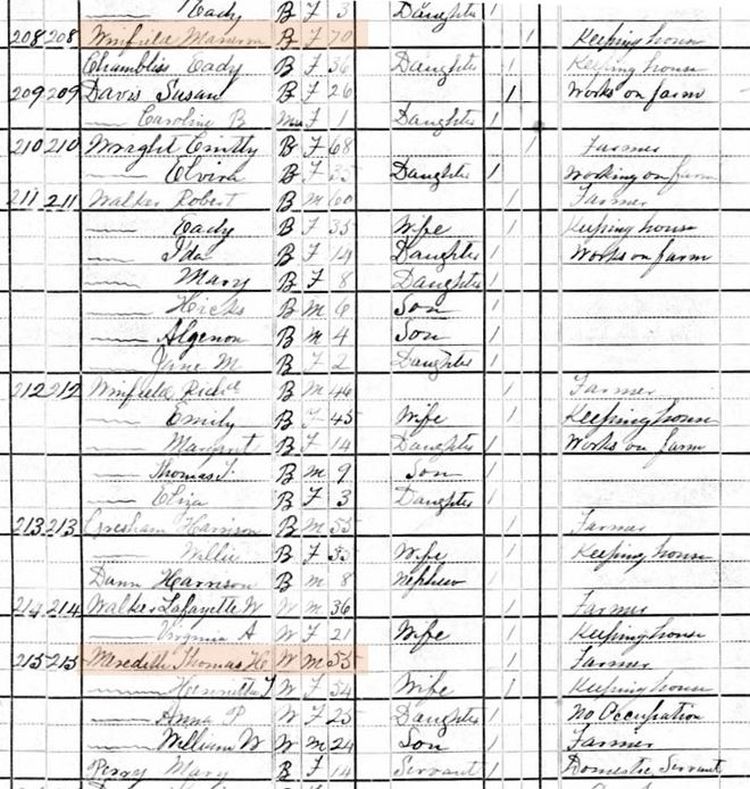

I decided to employ the cluster genealogy methodology. Minerva Winfield was found in the 1870 and 1880 censuses of Brunswick County, Sturgeonville Post Office. In 1870, she was the head of household #138. The closest white household was household #135, headed by a man named Thomas H. Meredith. His occupation was farmer.

I then researched Thomas H. Meredith for clues. Could he have been Minerva Winfield’s last enslaver? While looking at the censuses, wills, and probate records for members of his family, I soon came upon the will of his father’s sister, Nancy Meredith Walker. On December 15, 1856, Nancy Walker wrote, “2nd, I give my nephew Thomas H. Meredith my slave woman Manerva to him and his heirs forever.” [3]

Nancy further wrote, “4th, I give to my nephews Thomas H. Meredith and David W. Meredith all the remainder of my slaves (to wit) Harrison, Osborne, Anthony, Lucretia and her children, Daniel, Clay, George, James and Andrew . . .”[3] I had already uncovered that Osborne and Lucretia were two of Minerva Winfield’s nine found children. This cluster genealogy discovery confirmed Minerva Winfield’s last and previous enslavers.

This case highlights several important research tips:

- Cluster genealogy works! It may not work for all enslaved ancestors, but it is effective for many.

- Study the records of the family members of a potential (or verified) enslaver who lived nearby. Enslaved people were not only passed down to sons and daughters but also to nieces, nephews, and grandchildren.

- No. 2 means you must become familiar with the family tree of the potential (or verified) enslaver.

- IMPORTANT: If I had jumped to the slave schedules to try to pinpoint a Winfield as possibly being the last enslaver, I would have been led down the wrong road.

I will continue to dig further to figure out how Minerva Winfield was connected to my Brunswick County, Virginia ancestors.

Sources:

[1] [2] The estate of Benjamin Johnson, 1813, Brunswick County, Virginia, Brunswick County Will Book 8, p. 71.

[3] The will of Nancy Meredith Walker, Brunswick County, Virginia, Dec. 15, 1856, Brunswick County Will Book, Vol 16-17, 1853-1860, page 458.

Thank you Melvin for taking the time to outline this case study which shows researchers, both new and old, the benefits of this important research strategy.

I remember discussing this methodology with the community on the boards at AfriGeneas long before it was known by FAN Club. There were some brilliant researchers who congregated there and shared the wealth in the early 2000s and you were among them. African Ancestored research has come a long way with the advances of DNA but you’ve shown the community time and time again that the most indispensable tools in the researcher’s toolbox are critical thinking skills and the employment of proven research strategies like the one you outlined here.

May peace, blessings and many more rich discoveries await you in the New Year, my friend. Keep spreading the wealth.

Alane Roundtree

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much! I definitely remember the good ole AfriGeneas days!

LikeLike

Another educational post!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Awesome brilliant …exciting. So important to know what happens round the way.. neighborhood … zip code …who lives on the block… I too had stunning revelations. By looking at community directories and who were the aunties and uncles … keep inspiring us to both tell stories, listen, and be persistent. Love how you trace how those folks from Maryland and Virginia keep popping up in Mississippi. Also appreciate how and why this isn’t learned in schools and why our parents can’t tell us what they don’t know. We are all connected !

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree