Now that you’ve read the title, here’s what I mean.

Many of our ancestors have been trapped in a prison for the forgotten. Genealogy is the key that released them. Their names are unearthed and called. Their stories are being told to whoever wants to listen.

Genealogy has not only freed our souls held back by “historical ignorance,” but it has breathed new life into those forgotten ancestors and into us – the facts searchers! With genealogy, we gave them a new “Freedom Day,” a new Juneteenth in so many ways, and in turn, their stories and life experiences have allowed us to see what we are made of.

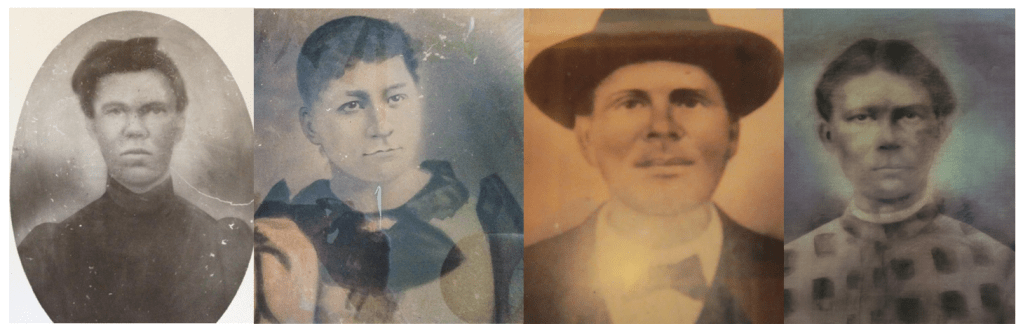

I think about how my father’s displaced great-grandfather – the father of Albert Kennedy of Leake County, Mississippi – was almost totally forgotten. For years, I could not determine who Albert’s father was. Since Albert and his sisters were known to look like they could pass, many had speculated that their unknown father was white. That brick wall was tall and sturdy for many years.

Now, after lots of DNA sleuthing, coupled with the long-omitted death certificate of Albert’s older sister, Mattie, his identity was found recently. He had a name. It was Melford Atkins. He was released from the prison for the forgotten.

Melford had been born to an enslaved mother and a white father in northern Virginia c. 1825 (Madison or Culpeper County), ironically about 75 miles from where I live now. He and at least two sisters were transported down South into Alabama for a short while, and eventually brought to Leake County, Mississippi c. 1851. There, he mated or “jumped the broom” with Lucy Kennedy, Albert and his sisters’ mother, who was enslaved nearby on Stephen Kennedy’s farm. Four children were born to them.

But Melford’s enslaver, Manson Atkinson, decided to move to Sugartown, Louisiana (Calcasieu Parish) shortly before the Civil War. His family never saw him again. His children were toddlers. After a while, Melford was slowly thrown into that infamous prison. Any memories of him faded. But genealogy freed him in 2022; it was his Juneteenth. His name is no longer a mystery.

I think about my mother’s great-great-grandmother, Fanny Barr. Also born into slavery in Virginia, possibly Henry County c. 1790, she was sold down to Abbeville County, South Carolina and became enslaved by a Presbyterian minister, Rev. William Barr, Sr. She was already an elderly woman when William Barr, Jr. took her, her daughter Sue Barr Beckley, Sue’s husband Jacob and their children to Pontotoc County, Mississippi in 1859. Her son, my mother’s great-grandfather Pleasant Barr, had been sold away.

Fanny survived the horrible institution of chattel slavery and was even found in the 1880 Pontotoc County census, reported as being 100 years old. After that, she too was slowly thrown into the prison for the forgotten. Genealogy freed her again, and in 2011, we honored her existence with this headstone below.

Since 1993, I have essentially freed many of my ancestors with genealogy. I understood the assignment that they wanted to be carried out. I gave many of them a second Juneteenth. For that, I am incredibly happy and proud. And like Harriet Tubman, I still have more to release from that prison for the forgotten.

To learn how to get started with genealogy, read African American Genealogy: Unearthing Your Family’s Past, From the Present to the Civil War.

To learn how to trace enslaved ancestors, read Slave Ancestral Research: Unearthing Your Family’s Past Before the 1870 Census.

Happy Juneteenth!

Wonderful post Melvin!

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the best blog posts I have EVER read. This was so powerful!

LikeLiked by 1 person