Federal census records are often deemed as the most important resource in genealogy research. Many new and seasoned researchers rely heavily on them. But other resources should be sought to get a fuller picture of ancestors’ lives and experiences. Federal census records cover every tenth year since 1790 (i.e. 1860, 1870, 1880, etc.), but what about the documentation of the in-between years? It’s challenging, but exhaustive research must be conducted to draw a clearer picture. And it takes time and persistence.

Often with enslaved ancestors, finding more documentation, after uncovering an ancestor in an enslaver’s will, estate record, deed, etc., is especially challenging. We must search for the records of the enslaving families to garner more details about our enslaved ancestors’ lives. This is paramount.

For example, an old family letter between members of Reid Family of Abbeville County, South Carolina revealed when my mother’s great-great-grandfather, Lewis, passed away. He was born about 1780 and had been enslaved by Rev. William Barr, Sr. in Abbeville County. On February 13, 1847, in a letter that Barr’s widow Rebecca wrote to her sister, Margery Reid Miller of Pontotoc County, Mississippi, she wrote, “I suppose you have heard that my old negro man Lewis is dead. He died in September. I hope was prepared for death.” [Transcriptions by Bob Thompson]

This provided me with Lewis’s time of death, September 1846. I would not have gotten that important fact from any other available records on Ancestry.com or anywhere else.

Great genealogical information can also be found in additional records such as:

- Chancery court cases

- Civil court cases

- Court minutes

- Other forms of court records available

- Civil War pension files (also from other members of the community)

- Probate/estate cases (reading the entire probate file)

- Newspaper articles

- Tax records

- Land records

- Freedmen’s Bureau records

- Slave narratives

- Plantation records

- Archived family papers (from the enslaving family) donated to a local archives or university/college

- Insurance records

- Church records

- Guardianship records

- And more

In other words, look for any records about or produced by the enslaving family. Pertinent details can be captured from them. Here’s another example.

In 2022, after nearly three decades of searching, I finally found the father of my father’s bio paternal grandfather, Albert Kennedy (1857-1928) of Leake County, Mississippi. Often previously purported to have been an unknown white man, Melford “Milford” Atkins was discovered to be the father of Albert and his sisters, Mattie, Leona, and Adaline. He was last enslaved by Manson Atkinson, who had relocated from Washington County, Alabama to Leake County, Mississippi by 1853.

Shortly afterwards, Melford mated with my great-great-grandmother, Lucy, who was enslaved on Stephen Kennedy’s farm nearby. Clues from census records indicate that Atkinson moved his family and enslaved people about 300 miles away to Sugartown, Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana right before or during the beginning of the Civil War. Melford was forever separated from Lucy and their four children. This case was presented in my Legacy webinar entitled, “How Three Types of DNA and Genealogy Uncovered the Long-Lost Enslaved Father.”

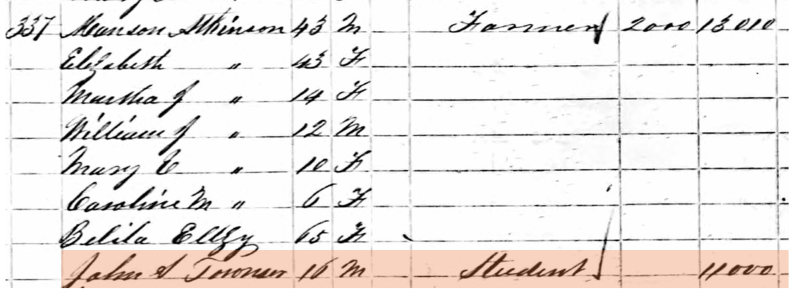

In FamilySearch’s new Full-Text Experiment tool, I found a chancery court case involving Manson Atkinson and his nephew, John A. Towner (Case #198). In the 1860 Leake County census, 16-year-old Towner was enumerated in his household. See below. The case involved the probate and guardianship of Towner from 1858 to 1863. Although Melford was not specifically named in the case, many other important details were uncovered that revealed more about the Atkinsons that affected Melford’s life. In other words, the details found in the case broadened my historical timeline of my great-great-grandfather’s life experiences.

In the timeline below, “NEW” represents new details learned from Towner’s chancery court case. Timelines help to highlight events of a person’s life by placing them into historical context. They also help to show the gaps in your research.

1825-1830

Around this time, Melford and his sister Harriet were born in northern Virginia, possibly Madison County, to an enslaved mother and most probably Murray Wilson (white) of Madison County, Virginia, per Y-DNA and autosomal DNA evidence.

1830

Around this time, Murray Wilson relocated to Fayette County, Ohio, where he married Angeline Binegar on September 17, 1835, per Ohio, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1774-1993. He was not counted (26 years old) in his father William Wilson’s household, per the 1830 Madison County, Virginia census.

1834

Around this time, Melford’s sister Ellen was born, and her birthplace was noted as being in Virginia in the 1880 Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana census (Ellen Towner).

1845

On a Clarke County, Mississippi tax roll, John Atkinson was reported as owning 15 enslaved people from age 5 to under 60 years old, and five young, enslaved people under the age of 5.

1850

By this time, Melford, Harriet, and Ellen were enslaved by John Atkinson, who was enumerated in the 1850 census and slave schedule in Washington County, Alabama. Atkinson also had a farm in nearby Clarke County, Mississippi, and his enslaved people also probably lived and worked in Clarke County, too. Future research: When and how did he acquire Melford, Harriet, and Ellen?

1853

Manson Atkinson was enumerated in an 1853 state census return for Leake County, Mississippi, which was certified on August 12.

1853

Around this time, Melford jumped the broom or coupled with Lucy, who was enslaved by Stephen Kennedy who lived nearby.

1854

Melford and Lucy had their first daughter, Mattie Kennedy Ealy, born around December 15 on Stephen Kennedy’s farm.

1856

Melford and Lucy had their second daughter, Leona Kennedy Pullen, born on Stephen Kennedy’s farm.

1857

Melford and Lucy had their son, Albert Kennedy, born on Stephen Kennedy’s farm. Also, John Atkinson died in Leake County, and Manson was appointed as the administrator of his estate, per June Term 1857 Court Minutes. An estate record for John Atkinson has currently not been found.

1858 (NEW)

Manson Atkinson was appointed guardian of his nephew, John Towner, per Towner’s chancery court case. He was orphaned and had been living with his grandfather, John Atkinson, as early as 1850, per the 1850 Washington County, Alabama census.

1860

Melford and Lucy had their last daughter, Adaline Kennedy Ealy. On July 28, Manson Atkinson was enumerated in the 1860 Leake County census and slave schedule with a personal estate valued at $13,000. Two months later, in a land deed dated September 28, Manson Atkinson sold 240 acres of land to William P. Gill for $800.

1860 (NEW)

On November 9, Manson Atkinson left Leake County and moved his family and enslaved people to Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana, according to John Towner’s chancery court case. This date is the day that Melford probably said “goodbye” to Lucy and their young children. Their youngest Adaline was just a toddler, under 1 year old.

1861

On April 12, the Civil War began when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

1861 (NEW)

Manson died shortly after they moved to Louisiana. According to John Towner’s chancery court case, he was noted as being deceased on a deposition dated December 20. Guardianship of John Towner was transferred to William P. Gill of Leake County. Towner had remained in Leake County due to a conflict with his uncle, as indicated in John Towner’s chancery court case.

1863 (NEW)

According to his chancery court case, John Towner died on 22 September at the age of 19 while fighting in the Civil War. His nine slaves were divided between his next-of-kin, who were Manson’s four children and Manson’s sister, Louisa Atkinson McLaughlin, who lived in Lauderdale County, Mississippi. One of them was named Duff, who was the mate/husband of Melford’s sister, Ellen, per her son’s death certificate. Louisa inherited Duff, and he likely never saw Ellen and their children again.

1865

On April 9, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union forces at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War.

1870

Manson’s widow, Elizabeth Williford Atkinson, was the head of household in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana. Grandpa Melford’s sisters, Harriet Atkins and Ellen Towner, lived nearby. He was not found in the census.

Conclusion

Realizing the gaps in your research from timelines helps to devise a research plan for additional research to try to fill in those gaps. Many records can assist with this endeavor and can paint an even more accurate picture of their lives and experiences. Just don’t give up.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Hi Melvin,

Thank you for sharing your research. It has been a guide for me in researching my family from Newton County, Mississippi.

We’ve hit a brick wall and want to turn more to DNA. Can you recommend a company for the Y DNA test?

Thanks

LikeLike

FamilyTree DNA does the Y-DNA test. They may be running sales over the Holidays. See http://www.familytreedna.com.

LikeLike