In 2015, several research buddies and I journeyed to Richmond, Virginia to research at the Library of Virginia. As I often recommend, I devised a research plan of names and records to explore. My focus was the records of Rev. William Parrott and his family. He was the last enslaver of my great-great-grandmother, Jane Parrott Ealy of Leake County, Mississippi, and her mother and siblings. He had moved them to Mississippi from Lunenburg County, Virginia shortly before 1840. I was armed with the names of Parrott’s family and his wife’s father, Julius Johnson of Lunenburg County.

My trip was fruitful. I photocopied a lot of deeds, estate, and other court records of the Parrott and Johnson families. As I studied them more in the comfort of my home, they turned out to be goldmines. However, I discovered something that shattered my heart into several pieces.

The goldmine included the discovery of Grandma Jane’s mother, Minerva. Rev. William Parrott and his wife Elizabeth had acquired her from her father Julius Johnson’s estate in 1824. Not only that, but the 5 December 1812 will of Julius’s father, Benjamin Johnson (Brunswick County), uncovered the name of Minerva’s mother, Rachel. She was my 4X-great-grandmother. Julius had inherited “one Negro woman Rachel and her child Manerva” and subsequently brought them to his farm in adjacent Lunenburg County. [1]

However, about a year later, Julius Johnson died. In 1813, while stationed at Norfolk, Virginia during the War of 1812, he became terribly ill, returned home to Lunenburg County, and died shortly afterwards in December 1813. [2] Matters of his estate had to be settled, and Rachel’s life horrifically crumbled even more. The 23 August 1813 inventory of Benjamin Johnson’s estate uncovered the names of four other children that Rachel had: Mary, Hubbard, Polly, and Nicholas. [3]

Fortunately, DNA technology has revealed that Nicholas Johnson resided near Canton, Mississippi (my hometown!) in Madison County after slavery, per the 1870 and 1880 censuses. My father shares DNA with at least 12 of his descendants. Rachel had been separated from him and her other children after Benjamin passed away. He had bequeathed them to his other children.

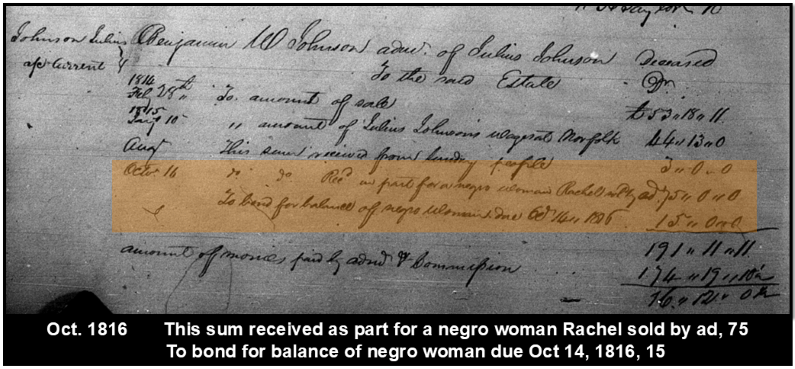

Heartbreak and anger overtook me as I studied the following court record below. It shows that the administrator of Julius Johnson’s estate sold Rachel in October 1816, another devastating blow to her life as an enslaved woman. [4] Grandma Minerva was about 4 years old. Who took care of her? The notation below brought tears to my eyes.

I can’t even imagine her pain of being separated from all five of her young children. American chattel slavery was abhorrently cruel. Researching enslaved ancestors not only takes time, perseverance, and dedication, but one must become emotionally prepared to handle the things they may find. It’s not an easy journey but a necessary one. Although Grandma Rachel was sold away to a place currently unknown to me, she is not forgotten.

Sources:

[1] The will of Benjamin Johnson, 1812, Brunswick County, Virginia, Brunswick County Will Book 8, pp. 69-70.

[2] Landon C. Bell, “The Old Free State”, Vol. 1 (Richmond: The William Byrd Press, 1930), pp. 281-283.

[3] The estate of Benjamin Johnson, 1812-1813, Brunswick County, Virginia, Brunswick County Will Book 8, p. 71.

[4] The estate of Julius Johnson, 1816, Lunenburg County, Virginia, Lunenburg County Will Book 8, pp. 54-55.

Wow although I know it probably took a lot of work to uncover this heartbreaking situation I know your ancestors are smiling down that finally someone has spoken their names and their truth

LikeLiked by 1 person