In 1996, I learned that my mother’s great-grandfather, Edward Danner of Panola County, Mississippi, was a Civil War veteran who served in the 59th Infantry of the United States Colored Troops. Edward was born about 1835 in South Carolina and died on 15 September 1878, leaving behind his widow, Louisa “Lue” Bobo Danner, with ten children to raise, eight of whom were fathered by Edward.

Years after his death, Louisa filed for a widow’s pension. The depositions contained in that file proved invaluable, providing details that made it possible to begin tracing Edward’s origins. Edward’s story became one of the central narratives of my first book, Mississippi to Africa, published in 2008. At that time, however, autosomal DNA testing was only beginning to emerge. Today, DNA evidence has opened the door to uncovering Edward’s long-lost family connections.

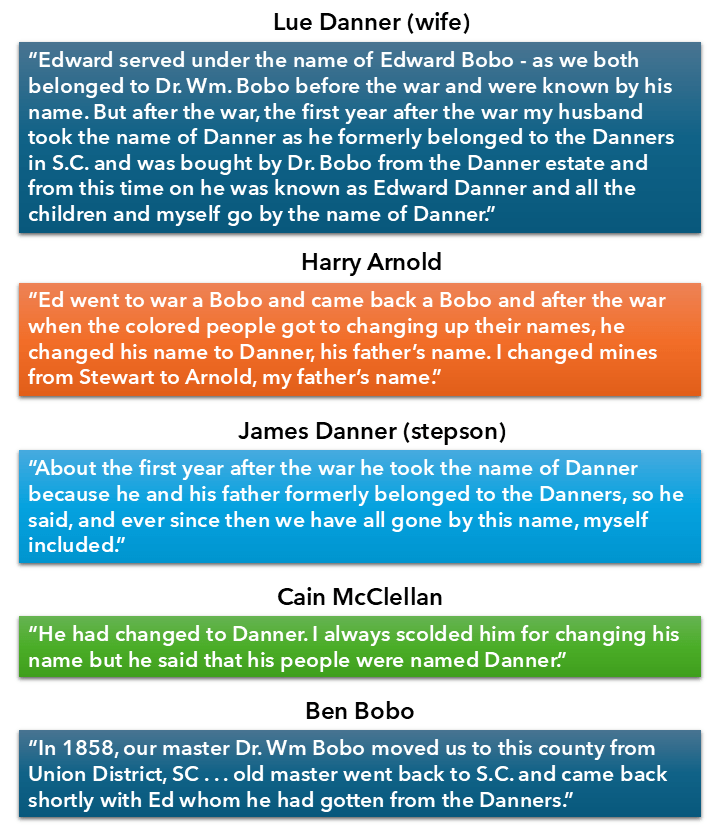

According to Edward’s pension file, he was purchased in 1859 by Dr. William Bobo from the “Danner estate” in Union County, South Carolina, and subsequently transported to Panola County, Mississippi. Multiple depositions within the pension file state that Edward adopted the surname Danner because both he and his father had been enslaved by the Danner family. This testimony strongly suggests that Edward had been enslaved alongside his parents, and likely siblings, while in Union County. The following depositions below provide critical insight into this connection:

After 1844, the only white slave-owning family bearing the Danner surname in Union County was headed by Thomas G. Danner Jr. The 1850 slave schedule shows that he enslaved eighteen people, several of whom were males within Edward’s probable age range. Thomas Danner Sr. had died in 1844, and Edward does not appear in the elder Danner’s estate inventory. Thomas Jr. died in 1855, making it highly likely that the “Danner estate” referenced by Grandma Lue was his estate. Unfortunately, no slave inventory from Thomas Danner Jr.’s estate has been located, leaving the identities of Edward’s immediate family members undocumented.

By 1860, Thomas Danner Jr.’s widow, Nancy Bates Danner, along with most of their children, had relocated to Saline County, Arkansas. They were accompanied by an enslaved woman named Harriet and her seven children. Using FamilySearch’s Full-Text Search tool, I located an 1855 deed in which Thomas explicitly allocated Harriet and her children to Nancy shortly before his death. While a complete probate file has not been found, the evidence suggests that most of Thomas’s enslaved people, including Edward, were sold after his death.

Several descendants of Harriet Danner, born about 1825, have taken autosomal DNA tests. They do not share DNA with my family, descendants of Edward, making it unlikely that Harriet was related to him. However, other DNA matches with deep roots in Union County, South Carolina began to surface in the years following the widespread availability of autosomal DNA testing. These matches provided critical new clues.

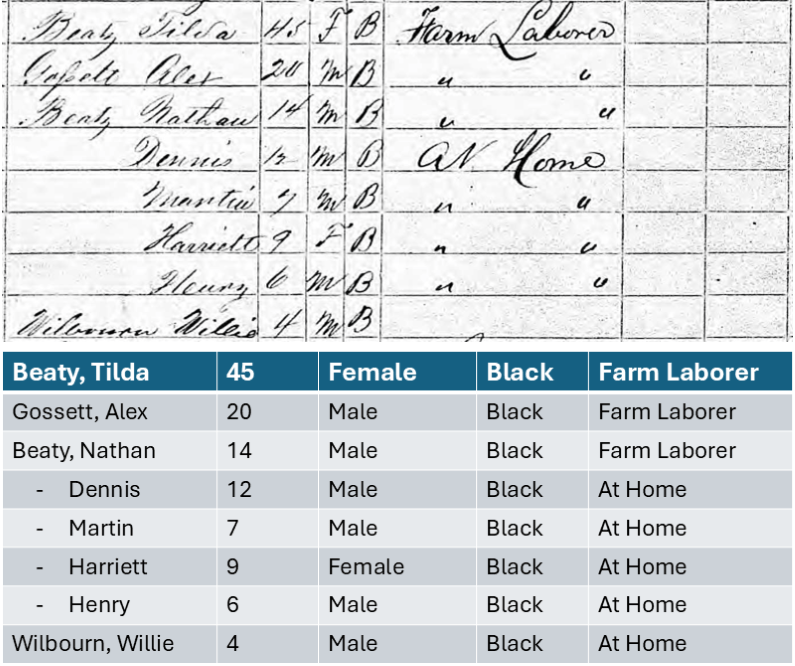

One woman who emerged prominently from this evidence was Matilda “Tilda” Beaty (also spelled Beatty), born about 1825. She appears in both the 1870 and 1880 censuses of Union County, South Carolina. In 1870, she was the head of her household, and by 1880 she was living with her son, Nathaniel “Nathan” Beaty.

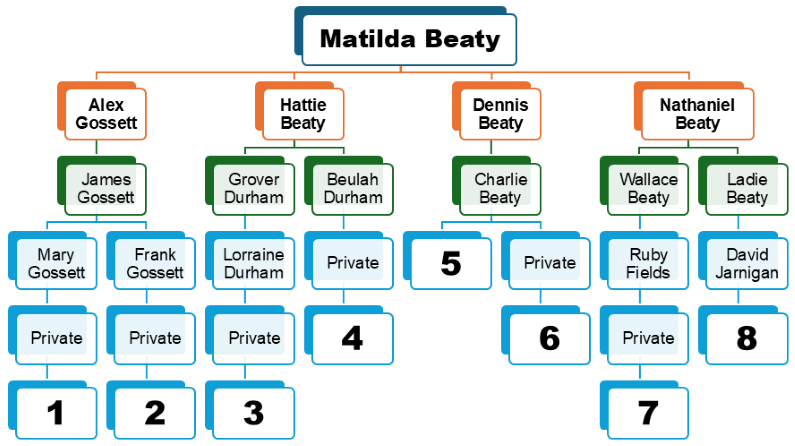

As demonstrated in the DNA chart below, at least eight of Matilda’s descendants share sizeable amounts of DNA, ranging from 19 to 65 centimorgans (cM), with my family, great-grandchildren of Edward through two of his daughters, Mary (my mother’s maternal grandmother) and Laura. Matilda’s eldest child, Alex Gossett, carried a different surname and had a different father than her other children. Because my family also shares DNA with Alex’s descendants, the genetic evidence clearly points to Matilda herself as the family link.

Census research further revealed that at least two of Matilda’s children, Nathaniel and Harriet “Hattie” Beaty, had migrated to Knox County, Kentucky by 1910. Knox County lies in southeastern Kentucky, firmly within the Appalachian region. Digitized Kentucky death certificates on Ancestry.com proved especially valuable.

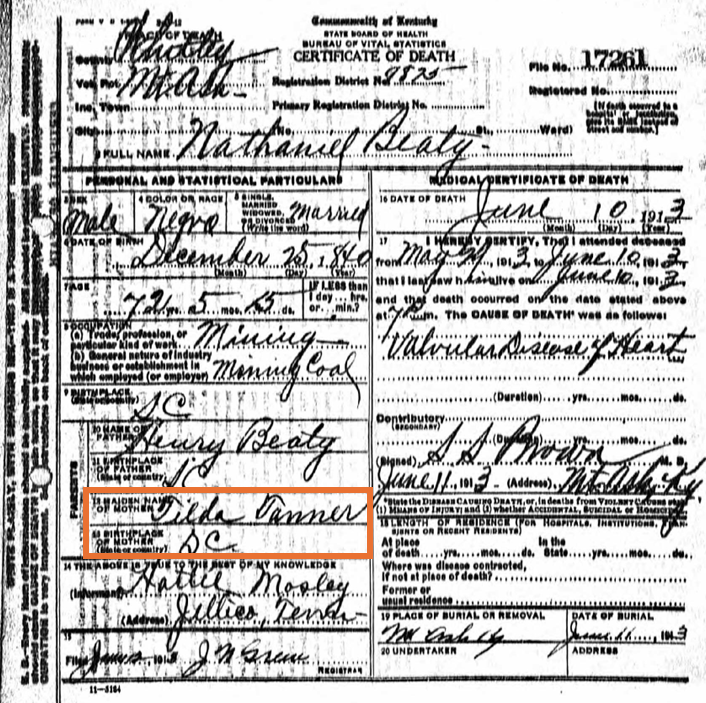

Nathaniel Beaty died in Whitley County in 1913. His death certificate records his mother’s maiden name as Tanner (or Danner) and lists his occupation as “mining coal.” See image below. The informant for this certificate was his only sister, Hattie Beaty Durham Mosley, Matilda’s own daughter. While death certificates are considered secondary sources, the fact that the informant was his only sister lends significant credibility to the information. No other record has provided a maiden name for Matilda.

The surnames Tanner and Danner were frequently used interchangeably, and no white Tanner families are known to have lived in Union County during this period. White Danner researchers have also frequently encountered the surname recorded as Tanner. Additionally, Edward Danner appears in the 1870 census of Panola County, Mississippi, where the census taker, whose handwriting was terrible, recorded his surname as Turner or Tarner. Taken together, the genealogical and genetic evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that Matilda Danner Beaty was likely Edward’s sister (or half-sister), from whom he had been separated after he was sold to Dr. William Bobo.

The story does not end there. Two of Hattie Beaty’s three children, Grover and Glover Durham, died in the 1920s in Hazard, Perry County, Kentucky, and their death certificates also list their occupation as coal miners. Nathaniel Beaty’s eleven children remained near Hazard, and his sons likewise worked in the coal mines. One of his sons, Martin Beaty, later settled with his ten children in Lee County, Virginia by 1940. Lee County lies in far southwestern Virginia, within the Appalachian Mountains. Online obituaries indicate that, as of 2014, some of Martin’s descendants still resided in mountainous Lee County, an area with a small but enduring Black population. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, 868 people, about 3.9 percent of the county’s population, identified as Black or African American. [1]

Following the Civil War, coal mining in Appalachia expanded rapidly as railroads, steel production, and urban growth fueled demand. Large numbers of Black laborers, seeking wages and greater autonomy, migrated to the coalfields of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. Coal operators actively recruited Black workers, and by the late 19th century, Black miners were a visible and essential part of the Appalachian workforce. Beginning in the 1940s, mechanization and mine closures sharply reduced employment, dispersing many of these families once again.

This discovery underscores how families torn apart by slavery can be reunited, at least on paper, through persistence, records, and DNA. Without genetic genealogy, I would never have known that branches of my family became coal miners in Appalachia. This journey is a powerful reminder of the unexpected places our ancestors’ stories can lead—and of the extraordinary power of DNA to restore lost connections.

Stay tuned for upcoming blog posts exploring Edward Danner’s long-lost family connections, uncovered through DNA evidence.

Your research is so detailed and careful. Wonderful storytelling. I was not aware that there were African American coal miners. I’m descended from white coal miners in Western Pennsylvania.

LikeLike